The Arnold Press: An Analysis

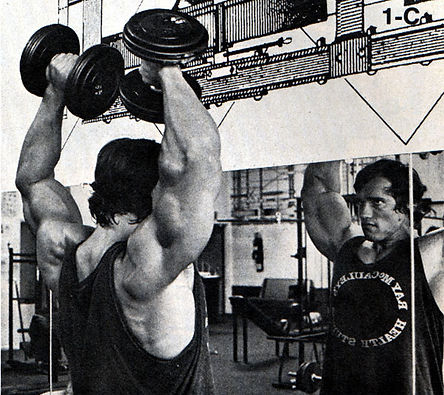

One of the most popular dumbbell shoulder exercises used in the gym is the Arnold Press. The popularity of the exercise being propagated by the esteemed bodybuilder; who developed and advocated this exercise, the great Arnold Schwarzenegger. The premise behind this exercise movement is that it employs a greater amount of shoulder muscle tissue and so has increased potential for overall shoulder development. With that premise at the forefront of our discussion let us now investigate and analyse this shoulder exercise and ascertain its validity as an exercise tool.

Before the legitimacy of the exercise can be determined we should first ascertain a basic understanding of shoulder anatomy and muscle function within the shoulder complex.

The shoulder complex consists of the shoulder girdle and its associated muscles. The shoulder girdle forms a ball and socket joint with which the humerus or upper arm bone interacts. This ball and socket joint allows movement through all three anatomical planes and axes. The bones that form this ball and socket joint are the scapula (shoulder blade) and the clavicle (collar bone). These bones meet at the acromion-clavicular joint and facilitate the insertion of the proximal end of the humerus. Although muscles such as the trapezius and pectoralis major have direct action on the shoulder joint we will focus on the three main muscles that allow abduction, flexion and hyperextension to occur. These three muscles also ‘cap’ the shoulder joint and when significantly developed create the ‘cannonball’ effect and the illusion of shoulder width and depth; that is so important in competitive bodybuilding.

As a group, the shoulder muscles are called the ‘deltoids’. They are named after the Greek letter ‘delta’; which is shaped like an equilateral triangle. The deltoids have three distinct heads which will now be discussed.

The first muscle of significance is the anterior deltoid which is located in the anterior region of the shoulder complex. This muscles predominant concentric function is to elicit shoulder flexion; an upward movement of the arm. The muscle also has secondary functions which are involved in shoulder abduction, transverse flexion and internal rotation. This muscle has its origins on the anterior border and upper surface of the lateral third of the clavicle and its insertion on the deltoid tuberosity of the humerus.

The second head of the shoulder muscle is termed the lateral deltoid and its location is lateral to the anterior deltoid and anterior to the posterior deltoid. Its main concentric function is to raise the arm to the side of the body in an abduction type movement. The origin of the lateral or ‘medial’ deltoid is located on the surface of the lateral third of the clavicle and its insertion arises on the deltoid tuberosity of the humerus; similarly to the anterior deltoid.

Finally, at the rear of the shoulder muscle structure, is the posterior deltoid. The posterior deltoid arises on the inferior edge of the spine of the scapula and inserts in a similar fashion as the other two heads, on the deltoid tuberosity of the humerus. Its primary concentric functions are shoulder hyperextension, transverse extension, transverse abduction & external rotation.

Other muscles that directly act on the shoulder are the rotator cuff muscles; the supraspinatus, the infraspinatus, the subscapularis and the teres minor; these muscles are involved in rotation and abduction and also play a role in the stabilisation of the shoulder structure. The teres major also has shoulder involvement as it plays a role in adduction and medial rotation of the arm.

Now a basic understanding of shoulder anatomy has been ascertained we must now peruse the claims that underlie the proposed effectiveness of the ‘Arnold press’.

The first claim that will be considered is that the Arnold press places more emphasis on the anterior deltoid than the ‘archetypal’ shoulder press. The starting position of the Arnold press involves the dumbbells being held in a pronated position with the palms and thus dumbbells being located anteriorly to the upper thoracic (pectoral region). In this position, the anterior deltoids would receive a degree of downward force as they resist the downward pull of the dumbbells. Therefore the anterior deltoid could be undergoing eccentric or isometric contraction. However, the extent of this contraction potential would be minimised or ‘amplified’ by the position of the hands. If the hand were to be held further away from the body, then the force would be placed increasingly on the biceps; and if the dumbbells were brought closer to the body then the effect on the anterior deltoid would be significantly decreased. So it seems this initial involvement of the anterior deltoid is singularly reliant on the technique being accurately applied, and any deviation from this ‘perfect’ technique will minimise the initial ‘theorised’ effect on the anterior deltoid.

Also with significance to this starting position, with the elbow angle being so significant, and the movement being so ‘rotational’, it is not likely that a resistance could be used that is anywhere close to the poundage’s that could be used in the ‘locked’ position of the standard dumbbell press. So it could be speculated that the Arnold press minimises intensity on the muscles due to the decreased weight potential and the increased complexity of technique.

The second factor that will be considered is that the Arnold press purportedly increases the range of motion that the shoulder muscles undergo. While this statement cannot legitimately be argued with, there are some questions that still arise. For example, if the purpose of a shoulder press, in any format is to work the ‘heads’ of the shoulder, then what possible benefit can be realised by working the muscles through an increased range of motion when that motion is in an extended position and detrimentally affects the amount of resistance that can be used both through elongation of the specific working muscles; and also through the increased technique difficulty. Argumentatively you could state that using a heavier weight in the ‘normal’ shoulder press would be far more ‘overload’ friendly and less injurious than its ‘Arnold’ counterpart.

Once the Arnold press has passed its first phase and the hands arrive laterally to the cephalic region then the press becomes very similar to the orthodox dumbbell press. However, remember that the weights you will use will generally be less significant; and so the stimulatory effect in this upper pressing phase will naturally be less significant than in the orthodox press ‘started’ from the lateral superior position.

The last aspect that will be discussed is the theory that the Arnold press strengthens the rotator cuff muscles and so can be a significant factor in injury prevention and shoulder ‘core’ development. Why there is no doubt that if the training stimulus is correct then strength development in the rotator muscles may occur; there has to be a ‘benefit to risk’ calculation. Due to the weights being used and the complexity of the technique, and the fact that the starting and finishing stage of the lift has concentric and eccentric components; any shortfall in technique could result in unwanted ‘torque’ being applied to the joint and muscles. Injuries may easily be realized. So the question arises as to whether the ‘real’ injury risks outweigh the minimal beneficial aspects of the Arnold press.

What conclusions can we draw from the above? The Arnold press has now become an ingrained aspect of many individuals shoulder training regimens. However, the validity of the claims attached to it are questionable. So should this lift become part of your programme or should it be relegated to ‘gym myth’?

This lift has its place in a training programme. As long as the technique is correctly applied and ‘egoistic’ lifting isn’t employed this lift does have some potential benefits. It is certainly a good secondary warm-up exercise. Bridging the gap between the initial warm up and the high-intensity component of a shoulder workout. It might also be a good exercise for sports specific applications where individuals such as wrestlers or mixed martial artist may find the complexity of the movement similar to grappling type movements but under resistance. The exercise can also be used as a ‘break from the norm’. Used every few workouts to break the monotony of the ‘standard’ shoulder workout. So the application is possible, but, with respect to the original premise behind this discussion, it is still a matter of conjecture as to whether this exercise has the capacity to stimulate or nurture significant gains in shoulder development as required by the competitive bodybuilder, above and beyond that of the orthodox dumbbell shoulder press. Science has yet to answer this question!